“There are only two kinds of decisions in life; those that are reversible and those that aren’t”

We’re continuing our exploration of Lee Cockerell’s leadership principles, learnt and embedded during his career in operations at the Walt Disney World® Resort, and as described in his book ‘Creating Magic’.

In today’s blog we turn our attention to the second strategy, “Break The Mould”.

In a nutshell, this strategy speaks to the importance of not being afraid to challenge the status quo and to do things differently. For Lee, this is not just about being open to trying new ideas, but also taking a disciplined look at your current practices (and even team structures) to determine if they’re still fit for purpose.

“Good organisational architecture not only keeps costs in line and maximises efficiency but also streamlines the decision-making process, enhances employee satisfaction, and facilitates creativity and innovation at all levels.”

Be clear about who’s responsible for what – “Every individual in your organisation should clearly and completely understand what they are responsible for, what level of authority they have, and how they will be held accountable. Each employee also needs to know what others are responsible for, what authority others have, and how others will be held accountable. Without clarity on those points, confusion and mishaps are inevitable.”

Clarity of understanding is a theme that Lee returns to a number of times in the book; in this context this relates to the role and responsibilities a person has. He cites this clarity of expectations that people are given, starting right at the recruitment and induction process, as one of the key reasons that he believes Disney gets it right so consistently.

He rightly goes on to point out that responsibility and authority go together – “If you give people responsibility without also giving them the necessary authority to carry out those responsibilities, you are setting them up for failure. So, make sure everyone knows exactly what outcomes you expect and what authority they have, install rigorous procedures for keeping informed.”

Make every position count – Lee shares questions that leaders should ask themselves about every role:

- Does this position create real value for the company?

- What would happen if we eliminated this position?

- What would happen if we re-distributed this position’s direct reports to others who can handle more responsibility?

- What would happen if this were a part-time position?

- What would happen if we outsourced this position’s responsibilities?

- What would happen if we changed our structure or processes so we no longer needed this position?

- What would happen if we automated this position so it became like a self-service, the way ATMs are for banks and websites are for booking travel?

Far too often I see employees who have worked in an organisation for a long time, being given promotions just because “they’re done their time” without any real conversation about A) are they capable to perform this role in terms of the technical skills, knowledge and behaviours required to make a success of it, and B) do we even need the role now?

Lee urges leaders not to fall into the trap of giving long-time employees, whose positions are no longer essential, new titles with no real responsibility, just to placate them.

Of course, there will be circumstances when you do have to let go of valuable people, but Lee stresses the importance of approaching these difficult situations in a professional and humane manner.

“Communicate quickly and directly with the person involved, explaining exactly why the position is being eliminated, give the person as much time as possible to find another job, either inside or outside the company, and offer to write a recommendation. When you are forced to let decent people go, treat them the way you would want to be treated in that situation: with dignity.”

Get a flat structure if you can – “Minimise the number of layers in your hierarchy, so you can deal directly with as many people as possible. Having a large number of people reporting to you has other advantages too. You get really good at delegating and it encourages you to hire the absolute best direct reports.”

A flat structure enhances productivity by streamlining decision-making processes, speeding up follow-through, and optimising communication. Fewer layers mean fewer mistakes, misunderstandings, mistranslations, and other misses.

“Having fewer kingdoms and fewer kings quickly leads to better results.”

I worry slightly that people might misunderstand Lee when he talks about the advantages of “having a large number of people reporting to you.” These can be realised if these individuals are smart, well-trained professionals who are capable of taking decisions, analysing the impact and learning from successes and failures.

Moreover, the way in which you approach delegation is critical to making this work; too much oversight from the leader can result in micromanagement and the loss of ownership on the part of the person being delegated to. On the flip side, we’re not talking abandonment here either! Getting this balance right is not the result of a scientific formula but taking into consideration the individuals’ experiences, the talents that they bring to bear on the task and, of course, the task and situation at hand.

Eliminate overwork – “People are not overworked; they are under organised.”

Consider carefully when you hear team members saying they haven’t got enough time to complete their job correctly. The culprit may well be the organisational structure. Ask yourself these questions:

- Is the overall structure getting in the way of productivity?

- Are departments or teams disorganised? Could I be organised in a better way?

- Are employees spending time on work that no longer has the value it once did?

- Can certain task be streamlined or even eliminated?

- Would employees work more efficiently if they were given more authority?

- Do employees need training in time management?

Can you eliminate positions that become superfluous and use some of the money you save to bring in additional roles and resources?

Time management is referred to here and it’s a topic that Lee rightly puts a great deal of emphasis on. We’ll be returning to it in detail in a later strategy and blog post, but it’s right that it’s mentioned here as a possible reason why it might not be a structural or organisational design issue but instead a choice that an individual has made to work in a certain way that is less than effective.

Rethink the meeting structure – Lee highlights that a typical symptom of a flawed organisational design is too much time spent in meetings. I’d certainly agree with that, although I see the challenge of too many unproductive meetings in organisations with both good and bad structures.

Firstly, identify the goals of your meetings and evaluate if those goals are being served by the current structure? “One productive meeting a month can be more valuable than one poorly planned meeting a week.”

The best way to evaluate the effectiveness of meetings is to get honest feedback from the people who attend.

-

-

- Ask if the meetings are held too often or not often enough?

- Ask if they drag on too long or too rushed?

- Ask if the right people are included in the meeting?

-

- Prepare a detailed agenda, and make sure that aims and outcomes are clearly identified. Send it out 48 hours in advance to give the attendees plenty of time to prepare.

- All meetings should begin on time whether everyone is there or not, and should end at the set time.

- Only invite people who need to attend.

Essentially there are two types of meeting, and knowing the difference will help you to determine who should be included. The basic purpose of one type is to give out information; the other is to solve problems.

Too many meetings are held just so the boss can keep in touch with their employees, a worthy intention, but one that can be accomplished in more effective ways, like having one-to-one conversations and visiting people at their desk.

Lee’s ideas outlined above provide sound advice for leaders who truly want to improve the quality of meetings they lead. For further inspiration, I’d recommend a blog by Michael Hyatt (https://michaelhyatt.com/so-many-meetings/) which provides further insights and tips on how to make the most of the meetings you facilitate.

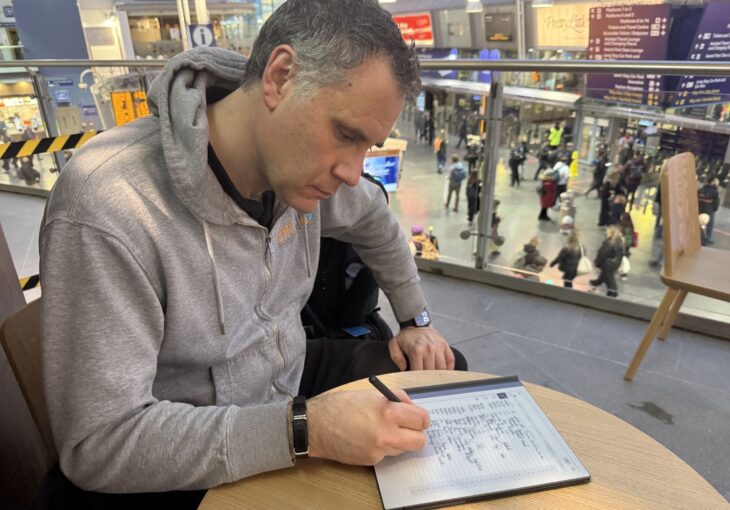

Anyone can take responsibility for change – If you have ideas on how to improve things, no matter what your role or status within your organisation, write them down and send them to the appropriate person.

Lee always told Cast Members, “Part of your salary is for giving us your opinions.” Everyone was encouraged and empowered to evaluate the structure on an ongoing basis and to submit recommendations in writing. “Remember, people on the frontlines see things you don’t!”

Be prepared to take risks – Two attitudes towards change can sabotage success. One is: “but this is the way we’ve always done it.” The other is: “we’ve never done it that way before.” Don’t fall prey to either of these.

Always look for a better way to do things, and don’t be afraid of upsetting people. If you have a good idea give it a chance. Remember, if it doesn’t work out you can always change it again.

“There are only two kinds of decisions in life: those that are reversible and those that aren’t.”

Expect Resistance – People do not like change and people will invariably fight structural changes.

Great leaders listen to those with sensible and serious objections and pay attention to reasonable arguments. But, when they think they’re on the right track, they don’t let the resistance of others stop them from doing what they believe in.

Because people naturally resist change, great leaders orient their people not only to expect change but to welcome it. In fact, they take it a step further – they train people to look for positive ways to initiate change.

Don’t try to win every battle – Leaders need to be persistent and determined in the face of resistance, but they also have to be flexible enough to fine tune their vision. Do not confuse being persuasive with winning at all costs. People respect leaders who pick their battles and can admit to being wrong occasionally.

You’re never really done – Even if you have a good organisational structure in place, don’t rest on your laurels. “Remember the changes you initiate might seem forward thinking today, but they will be tradition tomorrow. The innovative structure you put in place one year will be commonplace the next.

How do you know when to review your structure? Look for the signs:

People complain about red-tape; jokes about company bureaucrats become commonplace; employees say they feel like drones or robots; go-getters feel underused and their jobs are not challenging; leaders feel frustrated because they don’t have the authority to fulfil their responsibilities; creative people leave the company.

To summarise, the organisational structure is successful if:

- The operation runs fluidly in your absence

- The lines of accountability, responsibility and authority are clear

- Decisions are made easily and efficiently

- Information flows to all levels smoothly

- Answers get to the right people quickly

The current structure is not working if:

- People complain about wasted time, unclear roles, and miscommunication

- Too many people get involved in every decision

- Ineffective workers “hide” within the system

- There are too many or too few direct reports per manager

- Meetings are overly long, too frequent or unproductive

In part four of our exploration of Creating Magic we’ll cover one of the most crucial principles in Lee’s book “make your people your brand.”

“Most people think of a brand in terms of a product or a logo, but I soon discovered that in reality, your people are your brand. No matter how good your products and services are, you can’t achieve excellence unless you attract, develop and keep great people.”